Trofi

Trofi was a startup that my friends and I ran from April 2020 to October 2020. The goal was to explore the world of food distribution, and to see if we could make some groundbreaking changes in the area. Trofi was made as part of the first and second batch of the Mozilla Builders MVP Lab.

Looking back, it has definitely been a wild ride turning a hackathon idea to an incorporated company launch. Though the startup ultimately shut down, I'm glad I learned a ton about running a business and navigating the produce industry. I'll be sharing my experiences and takeaways, which can hopefully be of some help to you if you're intersted in these areas.

The builders lab

The origin story for Trofi is quite amusing. Basically, my friend Ryan went to me and asked if I wanted to hack on something with him. I said sure, and we started looking for an online hackathon (lockdown was in full swing by now). My mentor Shun mentioned the Mozilla MVP Builders lab so we decided to go for it. We got a call with Bart Decrem from Mozilla, who was unimpressed with our "digital giftcards app", but seemed excited about the dynamics of our team. So we basically joined a startup ideation program, assuming the whole time that it was just a regular hackathon. We quickly realized that we actually needed create a viable business idea ASAP, and that's where the story starts!

Exploration

We decided to hone in on the produce space, since we all had experience watching our Asian parents go to extreme lengths to get quality, niche produce. Moreover, this was during the peak of the groceries buying frenzy, when headlines were dominated by cases of farmers dumping milk and mushrooms due to the logistical dumpster fire that was the food distribution industry at the time. It was clear that this space was getting outdataed, so went to the local food terminal to see what it really was like.

For the next two weeks we travelled to the food terminal at unusal hours, to learn about the hidden machine that powers a huge part of how we eat. The Ontario Food Terminal serves the majority of the local grocery stores and restaurants in the Greater Toronto Area, so it was busiest between midnight and 2 am for produce to arrive when shops open up. We would drive down at 1 am on Tuesdays and Thursdays (the busiest days), and interview as many key people as we could. We broke into pairs, with one person asking questions while the other taking pictures, notes, and business cards. At the end, we would thank the interviewee and give them a $20 business card for their time.

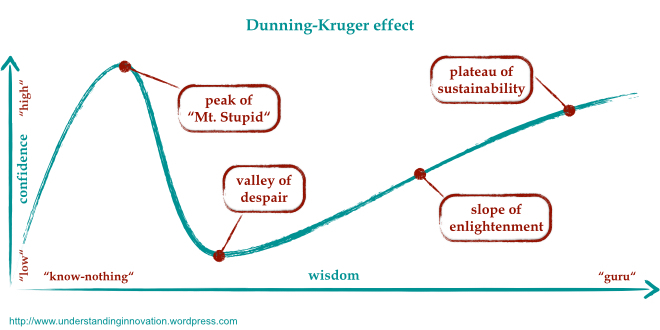

This bit of market research taught us that we in fact knew but a miniscule amount of what there is to know about this age-old industry. The lesson here was that for any project, the first step is to figure out the true unknowns (the things we don't know we don't know). After this, we were able to start answering some of those questions by prototyping with various MVP ideas.

The terminal

By this time, we had a pretty solid grasp about the inner owrkings of a food terminal. It consists of two sections: the loading bays uesd by multinational conglomerates, and the farmers market for smaller retailers. The loading bays mostly dealt with international produce: avocados, bananas, and mangoes. To make an order, you had to call a salesperson a few days in advance and place a quote for an amount anywhere from a box to several truck loads of the stuff. We were more interested in the farmer's market, which dealt with locally grown crops from various individual farmers.

The farmer's market consists of three main players: the farmer that grows the produce, the food distributor that sells the produce at the terminal, and the buyer that purchases the produce, either on behalf of a store or restaurant, or for themselves. Many local farmers also act as the distributor. The stuff here is exceptionally cheap; on a good day, you could buy a 40lb basket of bell peppers for $25, or a box of 12 english cucumbers for $1. Moreover, the food is exteremely fresh - you can expect an A grade tomato to have been picked within the past 3 days. Short of going to the farm, you are getting the stuff right at the source here. That's why most restaurants buy in bulk at food terminals instead of from another distributor, or even worse - the grocery store. There's a catch: to access the terminal, you need a buyer's card, which requires $250 and proof that you are buying as an incorporated business.

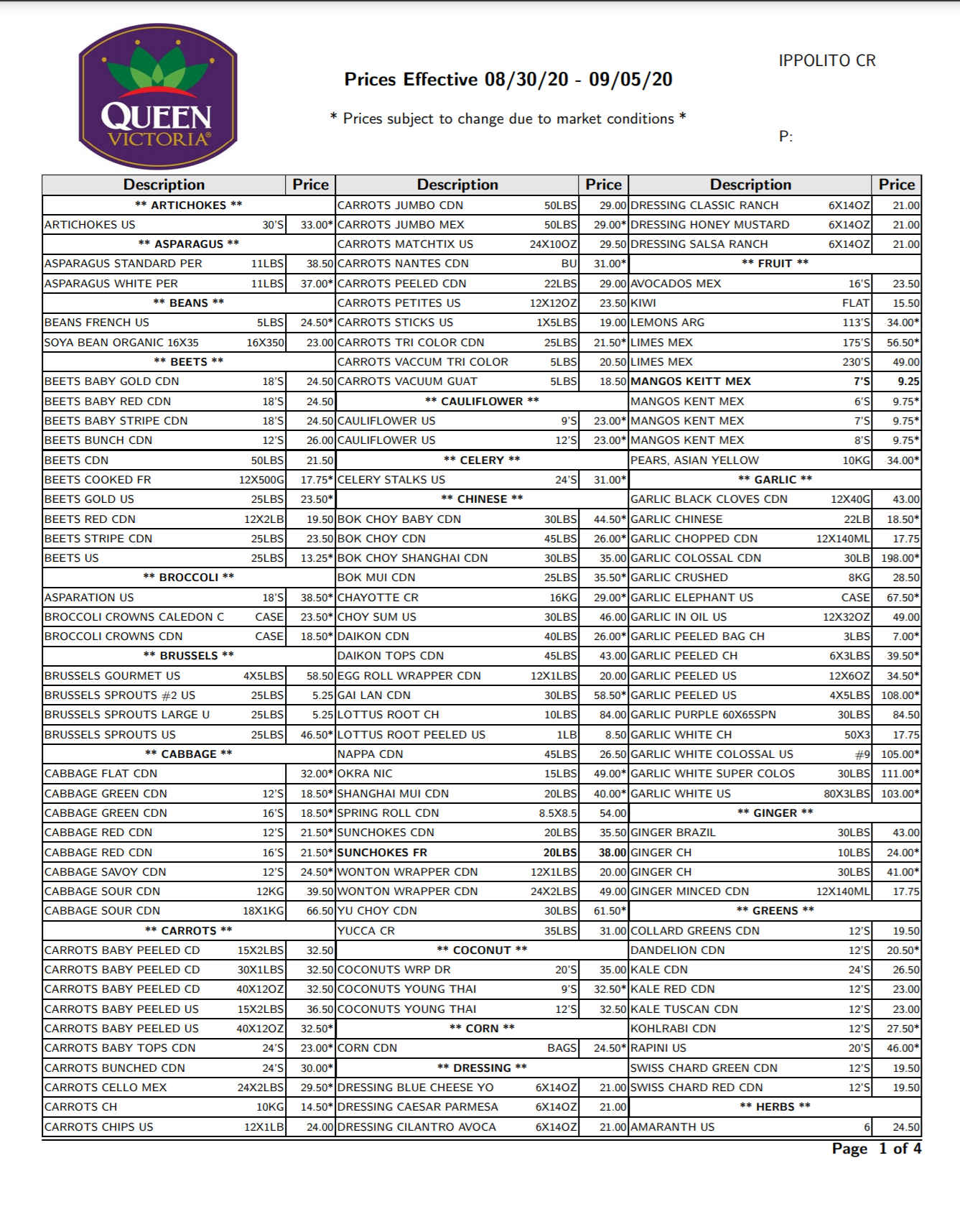

We also noticed that the dynamic at the market was very hands-on: prices are agreed upon on the spot, the seller personally comes to examine the produce, and discounts are given for long-time partners. Prices swing wildly by the day based on supply and demand, and distributors are extremely secretive about their prices - makes sense, since competitors have no way to differentiate their products from each other. We noticed that a seller even set up a wall of boxes between him and his competitor, so that they would not be able to overhear his negotiation prices. Also, everything was done very old-school: to make an order, you call or fax the distributor for a price, come in person to pick it up, and pay by cash.

Initial prototype

We thought that it would be really cool if we could have fresh produce delivered to the door at food terminal prices (like paying 20 cents for a cucumber!). So we started a produce group buy for some of our friends to get a feel of the process. Our mentors Bart, Bijan and Noah epmathized the importance of iterating quickly - that the point was to experiment with features and approaches instead of getting caught up with thoughts about scaling and design.

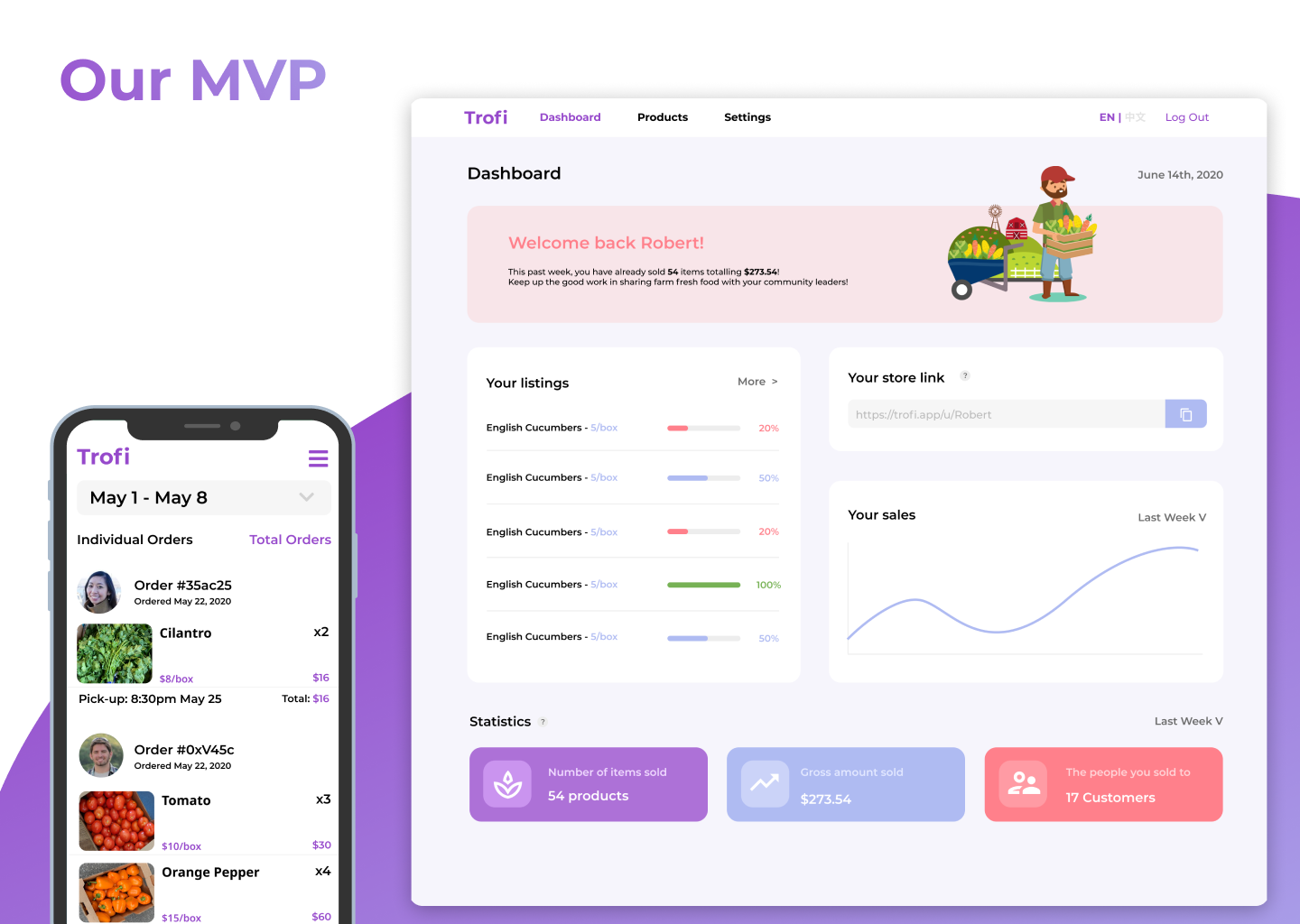

To get things running, we filled out a few forms, incorporated Trofi, and bought a buyer's card. On Tuesdays, we head down to the terminal, take photos, and get price sheets for the products for the day. We then called up our family friends who already take part in group buys, got them excited about the prospect of getting fresh, local food at an affordable price. We shared the prices on a Google Sheets doc and collected orders by hand. On Thursdays, we would drive down, pick up the produce, sort them at our homes, and drop them off at our customers' homes, where we would finally get paid at a 20% markup.

A few problems quickly arose. We initially underestimated the volatility of the produce prices and lost $200 on an order of tomatoes when prices spiked on a Thursday. Moreover, we got multiple complaints from our buyers about the quality of the produce. Factoring in the cost of gas, and the 6+ weekly hours we put into the operation, and it was clear that this was a very difficult operation. Unlike software products, scaling becomes logistically and economically challenging when factors such as storage, distribution and inventory come into play.

We continued with this experiment for a few weeks, building a network of food distributors and a database of price sheets. We also started working with existing group buy leaders, building a platform for them to track customer orders and list their own items alongside our selection. Though it wasn't a sustainable model, we were able to capture 5-digit revenue through our platform in 4 weeks, serving over 1000 customers and selling over 400 unique items. Overall, the process of growing something to have some not-insignificant traction was super exhilerating - it's definitely something I'll try to do more in the future.

The pivot

By this time, we had reached the end of the spring incubator. We demoed our product, process, and results, which generally pleased the organizers. We won third place in the lab, and got fast-tracked to the Summer MVP Lab. By this point, it was clear that we simply did not have the resources and time to compete meaningfully against the incumbents at the terminal. This being our first time taking part in an incubation program, we misinterpreted the expectations of the program and initially rejected Mozilla's offer. We assumed that we had to justify every dollar we spend from the 16k grant we got, which would make spending the money a lot more difficult. We also were not confident in our ability to get any meaningful results by the end of the program and did not want to mislead the program directors.

After a series of back and forths, we realized that we grossly misunderstood the nature of incubator programs like Mozilla Builders. These programs invest extremely early on - they get in at the pre-product and pre-idea, and oftentimes pre-team stage. The risk is so high that the program startups are almost always expected to fail. When we realigned our outlook to these expectations, we felt much less overwhelmed in trying to deliver short-term results. Also, we took the mentorship for granted; we assumed that if we left the program we could still ask our support network for help if the need arose. This actually isn't the case - founding programs like ours are very aware of the value of their mentorship networks, and won't let you access them when you leave them, unless specified otherwise.

After apologizing for the confusion we caused, we were back on good terms with the program, and spent the next few weeks ideating and prototyping ways to modernize the logistical process of the incumbent distributors themselves. This time, we were building saas and b2b, which was an entirely different process. We now had to tailor to the needs of each distributor we were pitching to, and had to push through the slow, beareaucratic process of selling a software service to a sales department.

We decided to create a way to digitize inventory management, which still mostly done on 20 year old software. The goal was to provide a clean and efficient platform that could replace the dozens of data-entry personnell that the companies used to punch orders on paper.

The the next step involves collecting market data from our users to create reports on marco-level trends in the produce sector, thereby eliminating the need for each company to spend millions on redundant and incomplete market research. Finally, we would implement IoT to POS at the terminal, gradually automating the inefficient physical transactions that take place at the terminal.

We reached out to dozens of CEOs at these distributors, following up to 5 times before they respond. The result of weeks of pitching and cold-calling was bleak; executives were only interested if we helped cut their bottom line. When we explained how the Trofi's modernization would do that, they wouldn't bite because we had no track record with any other company. At the end of the day, it seems that these distributors are perfecly content with their inefficiencies, simply their competitors are as well. It's not surprising, for an industry that still uses fax and calls as the main mode of communciation.

Conclusion

We tried to really shake up the food distribution in two ways:

Our first attempt involved building a decentralized alternative to the traditional system. That failed because we lacked the volume and infrastructure take on incumbents who capitalized on economies of scale.

Our second attempt attempted to modernize the distribution process for existing companies and terminals. That failed because the very mindset that let the industry become so ripe for disruption made it very difficult to make any meaningful changes within the space.

In the end, it seems that the best way to revolutionize ancient industries like this is to compete against the big players at their own game. Instead of working with existing taxi companies, Uber created a fleet of their own. SpaceX created a launch service of their own, instead of working with ULA or Boeing. Similarly, it would be much easier to build a smarter and more efficient distribution network than to convince decades-old leaders in adopting new tech. Sooner or later, this will happen, and the market will have to step up their game to stay relevant. Right now I don't have the resources to do this myself, but I can definitely see someone taking on this in the future.

Startup lessons

- Avoid tech when you start

During the prototyping stage, it's easy to get sucked into the building process. There's always some feature to add, bug to fix, design to make. But at the end of the day, a well-built product means nothing if there is no real demand for it. My mentors taught me to avoid tech like the plague - if there's a faster, no-code way to test something out, do that. By applying that mentality, I was able to avoid spending hours of grueling dev work that would've been put to waste when we pivoted after learning key lessons.

- It's okay to pivot

There's no shame in pivoting. In fact, a pivot is oftentimes a sign of adapting to a new reality or problem. Over time, our insights on the food distribution industry completely changed as we explored the true unknowns of our project. So we pivoted. This seems to be a common trend for startups and projects; learning is a never-ending process - all that matters is how you act on what you learn. Especially for early stage MVPs, pivoting is a great way for quickly trying out new ideas to see what works and what doesn't work.